Blog

February 4, 2026

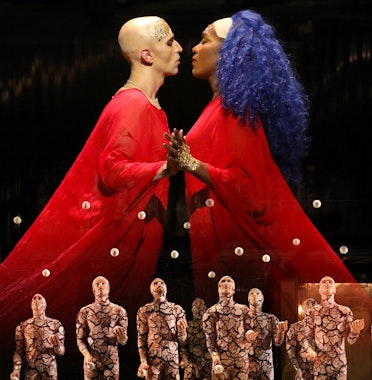

From Page to Stage: "Akhnaten"

Philip Glass’s Akhnaten is not simply an opera about Ancient Egypt—it is a ritual reawakening of a king and a belief system that died with him. Through sound, language, and ceremony, the work resurrects a pivotal moment in history, drawing directly from texts carved in stone and written on papyrus more than three thousand years ago.

These ancient sources, once intended for gods and the dead, now form the dramatic backbone of Glass’s score. Chief among them are two very different works: the Great Hymn to the Aten and The Book of the Dead. Though unrelated in purpose, together they illuminate the religious upheaval at the heart of Akhnaten—Egypt’s brief and radical turn toward monotheism.

At the center of the opera stands the Great Hymn to the Aten, one of the longest surviving hymn-poems dedicated to Aten, the sun-disk deity. While its authorship is uncertain, scholars widely attribute it to Akhenaten himself—or to a court poet writing under his authority. This attribution mirrors Glass’s portrayal of the pharaoh as both ruler and religious visionary. Akhenaten’s very name, meaning “effective for the Aten,” underscores the opera’s focus on devotion elevated to ideology.

Two versions of the hymn survive today: a shorter form found in five tombs and a longer version preserved in the tomb of the courtier Ay (spelled Aye in the opera). The longer hymn fills an entire wall with more than thirty lines of praise, varied in rhythm and structure. After Akhenaten’s death and Egypt’s return to polytheism, the hymn vanished from collective memory for centuries. Rediscovered in the 1880s, the text illuminated Akhenaten’s monotheism and later found new life in Glass’s Akhnaten, appearing in its original Ancient Egyptian at the close of Act II. The effect is less theatrical than ceremonial, as if the opera momentarily becomes a living temple.

Balancing this celebration of divine life is the opera’s preoccupation with death, shaped largely by the Book of the Dead. Despite its name, the Book of the Dead is not a single text but a vast collection of funerary spells composed between 1550–50 BCE, roughly. These writings were meant to guide the deceased through Duat, the Egyptian underworld, and were placed in tombs alongside other sacred texts.

In Akhnaten, excerpts from the Book of the Dead are heard during the “Funeral of Amenhotep III,” sung in Ancient Egyptian. The opera’s opening scene also draws from these texts, dramatizing the weighing of the heart against a feather—a ritual that determines whether the soul may pass safely into the afterlife. By beginning with death rather than birth, Glass frames Akhenaten’s reign as both an ending and a provocation.

The opera’s textual foundation extends beyond these two works. With the assistance of scholar Shalom Goldman, Glass assembled a libretto that incorporates Akkadian and Biblical Hebrew—languages that had never appeared in opera prior to Akhnaten. Rather than translating or modernizing these sources, Glass presents them as they were written, allowing history to speak for itself. The result is an opera that feels less like narrative drama and more like ritual reenactment, as though Aten is summoning pharaohs from the past to occupy the stage once more.

Seen through the lens of the opera, Akhnaten, history feels startlingly contemporary. Three thousand years after his reign, Akhenaten’s vision of a single god is no longer heretical but foundational to much of the modern world. The opera reminds us that this belief was once radical, contested, and deeply disruptive. Through ancient texts and modern music, Akhnaten preserves the memory of a world in transition—one in which faith, power, and identity were renegotiated at enormous cost.

Click here to get tickets to see Akhnaten.

To learn more about the Book of the Dead, check out our podcast with The Getty Villa's Egyptology Curator, Dr. Sara Cole: https://soundcloud.com/laopera/opera-in-the-community-akhnaten-with-dr-tiffany-kuo

/03-cosi/_dsc0996_pr.jpg?format=auto&fit=crop&w=345&h=200&auto=format)