Blog

May 12, 2025

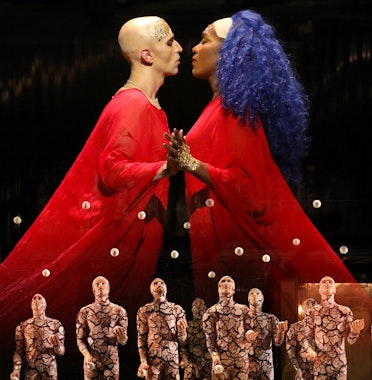

Verdi: Transforming Society's Rejects

A Note from Music Director James Conlon

“Everyone cried out at the idea of putting a hunchback on the stage; well, there you are. I was very happy to write Rigoletto…and it is my best opera.” (July 26, 1852)

And Verdi still thought so 35 years later: “I could write another Otello, but never another Rigoletto,” proclaimed the 74-year-old Giuseppe Verdi after the stunning premiere of his penultimate opera in 1887. Having transformed Italian opera over the course of the 19th century, it is fascinating to consider this statement. He was referring to the first of what are commonly known as the three middle-period masterpieces, written in an incredibly short period of little more than two years. Rigoletto was premiered in March of 1851. Il Trovatore and La Traviata were both produced for the first time five weeks apart in 1853.

These three operas have historically been the most popular and the most universally loved of Verdi’s work. As a measure of this it is interesting to note that, at the time of this writing, all three of these operas are among the dozen most-performed works in the history of the Metropolitan Opera. Explanations of their durability are in no short supply. First is the seemingly unflagging inspiration of melodic invention. These operas abound in great arias and duets whose melodies could be grasped immediately by the public, whistled, hummed and sung on a popular level, and admired and studied after a hundred hearings by musicians and musicologists. Their “formula” was simple, even simplistic, but their genius of how they endear themselves and speak directly from the heart of the character on stage to the emotions of the listener is the quintessence of Italian opera. Their brand of romanticism summarized all that had transpired in previous the previous half century of operatic theater. They are situated in the vestibule to the future, which Verdi himself sets out in these works. Like the head of Janus, these works look backward, in some ways for the last time, but irrevocably point forward.

So much has been written about these works that it is impossible to add much that is new. For that reason, I would like to isolate one aspect of a common characteristic of the three masterpieces which I believe is sometimes overlooked by those who might consider these works to be “old fashioned.” They are, in fact, in the context of Italian theater of the early 1850s, not just daring, bold and shocking, but, in their way, revolutionary.

Verdi’s theatrical genius led him ceaselessly to search for interesting dramatic material. Europe had been rocked by political upheaval and revolution in 1848, and the shock waves were keenly felt by the composer. His lifelong pursuit of audience appeal led him to eschew much of the formulaic opera libretti of the past century. He foreswore mythology, ancient Greece, Rome and even Italian subjects. French, English, German and Spanish sources abound, and it is from Victor Hugo, Antonio García Gutiérrez and Alexandre Dumas that he found the sources for this extraordinary trilogy.

The common thread that ties these works together is their presentation of protagonists who belong to categories of contemporary society’s rejected persons. Verdi saw the potential for explosive dramatic material in the lives and fates of a misanthropic hunchbacked jester, a desperately crazed Romani woman—member of an ethnic group despised and rejected throughout Europe—and a Parisian sex worker. The genius is not only in the choice, but in the rendering. We empathize with Rigoletto despite his physical and moral ugliness, because of his tender love for his daughter. Azucena’s plight (however farfetched the plot) wins our hearts, despite her degraded and reviled origins. Verdi allows them to point an accusatory finger at their societies for their abject existences, blaming their own vileness on their surroundings. Violetta dies of consumption but turns the tables on the hypocrisy of her society, proving that a woman “of fallen virtue” can be far more capable of true love than the proponents of bourgeois morality. In his soliloquy “Pari siamo,” Rigoletto hurls invective at his world, as a subject of a duke and his courtiers: If I am wicked, it is due completely to you. The idea that the criminal or outcast is bad, not of their own doing, but of their victimization, is one we associate with the 20th century, placing Verdi and Victor Hugo (whose play provided the opera’s subject matter) far ahead of their times.

In choosing Hugo’s Le roi s’amuse (“The King Enjoys Himself”), Verdi knew exactly what he was doing. After all, Hugo’s play is a thinly veiled assault on French royalty and mores. It was closed by the authorities the day after its premiere at the Comédie-Française in 1832. Its depiction of the 16th-century French king, Francis I, though essentially historical, was deemed offensive. It was impermissible to portray a member of the royalty as a roué. His libertine ways are those of Don Giovanni, moving from the daughters and wives of courtiers to a chaste, innocent young woman to a romp with a prostitute. The father in classical theater usually demanded a noble bearing, and it was incongruous that he should be represented by a court jester, who would normally be a comic or secondary character. Hugo did not even spare the mother of King Louis Philippe I (1773-1850), tangentially referring to rumors of her escapade with lackeys.

/05-Rigoletto/thedallasoperarigolettoflubackerhighlights-025_PR.jpg)

It isn’t necessary to go further to illustrate Hugo’s penchant for acid social criticism. Verdi saw his opportunity to turn convention on its head by depicting a king as immoral, and his court jester, a hunchback, as tragic. In the minds of his contemporaries a deformed man might be appropriately presented in a circus but, in general, would be considered unworthy of the stage, and certainly not as a tragic protagonist.

Verdi started to work, sketching a scenario corresponding to the original, featuring King “Francesco” of France, entitled La Maledizione (“The Curse”). The libretto of the opera we know is the end result of a chain of revisions necessitated to gain the authorities’ approval of the work for performance. The censors, always severe, were particularly concerned after the 1848 political upheavals that the theater was a venue for influencing the public and were potentially dangerous politically. Through a successive series of modifications, the King of France became the Duke of Vendome, subsequently diminished to Duke Vincenzo di Gonzaga of Mantua, and eventually retaining only his title without a name. The censors took exception to the opera’s title, which seemed blasphemous. The chief of the Venetian police “deplored” that the celebrated maestro and his librettist Francesco Maria Piave were not able to find a better vehicle for their talents than a libretto of “repulsive immorality and obscene triviality.”

The degree of Verdi’s courage and boldness can be measured by the censors’ reaction. And two years later, again in Venice, he was ready to go further, by portraying a consumptive sex worker as a heroine, a symbol and incarnation of generous and total love.

Mid-18th-century Europe’s burgeoning humanism not only allowed the possibility of sympathetic portrayals of humanity’s underdogs, but actually seemed to have ignited Verdi’s genius. In his two previous operas he cut a path. Luisa Miller (from Schiller) is the tragedy of the genuine goodness of the humble trampled upon by the aristocracy. Stiffelio, the opera that directly precedes Rigoletto, portrays a minister’s struggle with an adulterous wife and her lover. It is a fascinating work, dramatically as daring as its successors and, musically, a necessary preparatory step. The three middle-period masterpieces had not burst forth from nowhere, they had been percolating over time.

Musically, Rigoletto demonstrates a significant advance in breaking down the traditional fixed forms of the earlier bel canto period. The conventional structure of the “scene and aria” and closed forms still abounds, where musical forms often determine aspects of the text. But the word (Verdi’s parola scenica, the “scenic word”) is increasingly emerging as the determinant of the musical organization. Nowhere is this more evident than for the protagonist, whose music could be described as constantly developmental: halfway between aria and recitative (in a form known as arioso). The form is determined by the dramatic situation, not for fulfilling traditional expectations. This is one of the hallmarks of the future. It is fitting that the most audacious character on the stage also is the inspiration and conduit for the most advanced musical expression to date. Traditionally, there was a strict division of labor between recitative (where the word is dominant, declaimed relatively non-melodically to a simple orchestral accompaniment) and the aria (where the melodic line is dominant, and the text subservient).

Oversimplified, the protagonist’s physical ugliness yet rich inner being is expressed by music predominantly belonging to the future. The music of the outwardly handsome, amoral, high born Duke of Mantua belongs to the past. He sings a ballad at the beginning (where he sets out his philosophy of seduction) at the beginning and a frivolous ditty (an example of classic Freudian projection) at the end. Though he is given a proper aria and cabaletta in Act Two (where he is only fleetingly and superficially genuine), it is in an utterly and significantly conventional form, though inspired before its formulaic end. The immediate and lasting universal success of the Duke’s “La donna è mobile” proved that even while portraying flippancy and callous entitlement, Verdi could make a lasting impression.

Gilda progresses from “standard” duets with her father and the disguised Duke and an ornamented aria (“Caro nome”) in Act One, through a developing equilibrium between word and song after her seduction in Act Two, into “maturity” in the final act where she assumes her father’s prose and declamation. Vocally her music transforms her, starting from lighter trills and roulades to finishing with the demands of a dramatic soprano. The musical texture passes from a series of closed pieces to a predominantly symphonic structure in the last act, fully unleashing the orchestra at last in the symbolic fury of a storm.

Finally, there is a developmental step in the enhanced use of a leading motive. The curse of Count Monterone, the father of one of the Duke’s mistresses, is the central dramatic event; hence Verdi’s intended original title. It is expressed by the rhythmic repetition of a single note and is freely used throughout the opera both to accompany Rigoletto’s obsession with that curse, and to mark its realization in the course of the drama. The Rigoletto prelude has a single motive, that of the curse (“maledizione”). Menacing and ominous, its premonitory character is only momentarily repressed by the superficial festive music of the first scene.

But Monterone’s curse, hurled at he “who laughs at the sorrow of a father,” cannot be simply brushed aside. It befalls Rigoletto, not because Monterone has supernatural powers, but as a great dramatic irony. The hunchback’s entire world is his daughter and, living as he does —a “serpent” in a court of iniquity—he and the beauty of his paternal love are doomed from the beginning.

Both Rigoletto and Monterone are not so much antagonists as two outraged fathers, whose daughters have been seduced by the Duke. Just slightly over two years before Rigoletto’s premiere, Verdi wrote Luisa Miller (1849), drawn from a play by Friedrich Schiller. Like Rigoletto, it is essentially the tragedy of two fathers who lose their children. With this, and his 1847 adaptation of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, Verdi was preparing his way for his middle-period masterpieces through two great authors whom he loved.

Our contemporary society has not ceased to define certain persons as outcasts, to assign second-class citizenship to some, to remain indifferent to poverty, to mock the physically challenged and to mistreat those who are vulnerable. The double tragedy is indeed relevant in our time. Despotic rulers continue to mistreat vulnerable individuals, and the crushing end, portraying Rigoletto and Gilda’s fate, is only deepened by contrast: the Duke continues on his path, untouched by and indifferent to the fate of others.

Neither Hugo, who described himself as a “free thinker,” nor Verdi, an acknowledged anticlerical agnostic, had forgotten the Sermon on the Mount, and let is echo resonate through the actions of those who did not heed it, and illustrates it to us with a tragic object lesson about a hunchbacked protagonist.

/03-cosi/_dsc0996_pr.jpg?format=auto&fit=crop&w=345&h=200&auto=format)