Blog

October 14, 2025

100 Years of "The Phantom of the Opera"

On May 20, 1896, a tragedy took place at the world-famous Paris Opera House (the Palais Garnier) that still reverberates in the public consciousness today. One of the counterweights of the auditorium's grand chandelier broke loose and fell onto a concierge, killing him and injuring several others. The shocking event led many Parisians to believe that the opulent Palais Garnier was haunted.

This superstition would be revisited and introduced to new audiences on the morning of September 23, 1909, when readers of Le Gaulois newspaper opened their copies to find a new serialized story. The series was written by Gaston Leroux, already well-known for his suspenseful fiction—especially his acclaimed detective novel, The Mystery of the Yellow Room. Leroux’s new story, The Phantom of the Opera, took direct inspiration from the chandelier incident. It followed soprano Christine Daaé’s fateful encounter with a mysterious, disfigured admirer who lurks in a hidden lair beneath the opera house. In one of the story’s most iconic moments, the Phantom, consumed by rage, drops a chandelier onto the audience with fatal consequences.

The series was published as a novel in 1910. While Leroux’s earlier novel had been well received, Phantom initially failed to capture the same audience, with many readers preferring the mystery and intrigue of his earlier story over the speculative horror approach he took in Phantom.

Early filmmakers, however, saw the potential in depicting Leroux’s eerie atmosphere onto the big screen. The first of these was Ernst Matray, who directed his adaptation in Germany in 1916. The script was written by his then-wife, actress Greta Schröder (whom film buffs may recognize as the leading lady in F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu), and starred Nils Olaf Chrisander as the Phantom. (Unfortunately, this film is now a phantom in itself; it is considered a lost film, with only promotional material in trade magazines left to prove its existence.)

It seemed Phantom was destined to become a forgotten serial, but Leroux ensured his story left a lasting mark. While on vacation in Paris, Carl Laemmle, president of Universal Pictures, expressed admiration for the Palais Garnier. Leroux seized the opportunity to gift him a copy of The Phantom of the Opera. Laemmle read the novel in a single night and purchased the film rights the very next day.

Laemmle’s enthusiasm may have stemmed from knowing exactly who should play the Phantom: Lon Chaney, “The Man of a Thousand Faces,” renowned for his transformative makeup skills. Chaney had already become a household name thanks to his portrayal of Quasimodo in Wallace Worsley’s 1923 adaptation of The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

The Phantom of the Opera was originally slated for a 1924 release, but it would be delayed as production soon descended into chaos. According to director of photography Charles Van Enger, tension arose due to the cast and crew's dislike of director Rupert Julian due to creative differences and people showing loyalty to Lon Chaney. Chaney and Julian would constantly clash, and the two eventually stopped speaking altogether. Van Enger became the go-between, relaying Julian’s notes to Chaney, who responded to every comment with: “Tell him to go to hell.”

Van Enger also defied Julian's vision during one of the film’s most memorable scenes. Julian wanted the screen to fade to black during the chandelier's fall, but Van Enger kept a soft light on so the audience could fully witness the spectacle—a decision that preserved one of the film’s most striking visuals.

One area where Julian had no input was the Phantom’s makeup. Chaney, always pushing his craft, aimed to top his transformative work in Hunchback. He contorted his face into a skeletal visage, reshaping his nose with putty and inserting wire loops into his nostrils to pull them upward—an effect that often caused bleeding. But Chaney endured the pain, determined to bring Leroux’s Phantom to life. The final result was so horrifying that audiences reportedly screamed at first sight. Actress Mary Philbin, who played Christine Daaé, hadn’t seen Chaney in full makeup prior to filming their unmasking scene, and her terror on screen was genuine.

By late 1924, a rough cut of the film was finished, running nearly four hours. Editors worked to reduce it to around 90 minutes for its January 26, 1925, Los Angeles premiere. The film was accompanied by a score from Joseph Carl Breil, though, like the 1916 adaptation, this music has since been lost.

Unfortunately, the premiere was not the hit Laemmle had hoped for. The New York premiere was canceled, and the film went back into production for reshoots.

Rupert Julian would not return to direct the re-shoots. Edward Sedgwick took over, and he pivoted the film to become a combination of action and dark romance, adding new subplots for comedic relief. However, this new version bombed at its San Francisco premiere and was booed by audiences.

Universal then tasked in-house filmmakers Maurice Pivar and Lois Weber with salvaging the project. They edited a third version, removing most of Sedgwick’s material and reinstating scenes from Julian’s cut. This final version was met with positive reception. Audiences finally resonated with the film’s visual innovation, striking makeup, and eerie atmosphere that has kept it relevant for a century. (A subsequent version was released in 1929 with newly shot sound dialogue, but that cut has also been lost.)

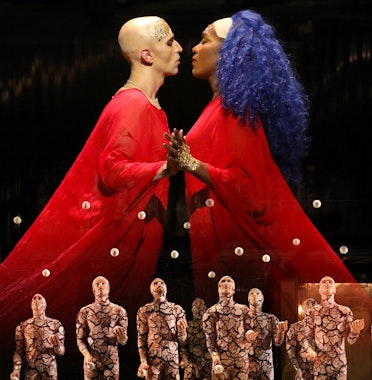

It is Chaney’s unforgettable Phantom that truly secured the story’s place in pop culture. His performance inspired renewed interest in Leroux’s original novel. Among those inspired was playwright and director Ken Hill, whose 1976 musical Phantom of the Opera directly influenced Andrew Lloyd Webber’s blockbuster 1986 stage adaptation. Lloyd Webber’s musical further cemented the Phantom’s place in pop culture, with its iconic title track and “The Music of the Night” being instantly recognizable to audiences worldwide. The crashing chandelier became the unforgettable final image of Act One.

For a story plagued by poor reception, production issues, and lost adaptations, it would have been easy for The Phantom of the Opera to fade into obscurity. But something about Leroux’s tragic, haunting tale has continued to resonate. Thanks to Chaney’s chilling portrayal and generations of fans, Phantom has endured for over a century, and it shows no sign of vanishing anytime soon.

/03-cosi/_dsc0996_pr.jpg?format=auto&fit=crop&w=345&h=200&auto=format)