Blog

April 29, 2025

Margarita the Red: A Life Lived for Art and Revolution

In the sweltering heat of a Spanish summer, you’d do just about anything to find relief from the oppressive sun. You might duck into an ice cream parlor, slip into the shade of a café, or escape to the beach, letting the waves cool your burning skin. Some choose the comfort of a quiet restaurant, others the buzz of a bar. It was the latter that Spanish actress and director Margarita Xirgu chose on a blistering day in 1926—seeking shelter not just from the heat, but from the weight of a world that rarely made room for people like her.

Inside that dim, cool bar, Xirgu caught the eye of a young poet who was also hiding from the midday blaze. His name was Federico García Lorca. At the time, he was drowning his sorrows after his first play had been publicly mocked and quietly buried. No conventional theater director would risk producing another of his scripts. But Xirgu was not conventional. She was electric.

From the moment they met, there was a spark—an instant recognition. They were kindred spirits, bound by their rebellious politics, their love of art, and their queerness in a country hostile to both. What neither of them knew that day was that their brief refuge from the sun would mark the beginning of one of the most important artistic friendships in Spanish history.

The fire they ignited together burned brightly and briefly, but its warmth still lingers today. Their collaborations—Mariana Pineda, Blood Wedding, Yerma, Doña Rosita the Spinster—are now considered classics of 20th-century theater. And after Lorca’s brutal assassination in 1936, it was Xirgu who carried the torch, refusing to let his voice be silenced. While Lorca’s name is now widely celebrated, Xirgu’s has faded into near obscurity. When she passed away in 1969, not even an obituary marked her death.

So, who was this overlooked revolutionary of the stage? And why must her name be remembered?

The Rise of a Revolutionary Actress

Born in 1888 to a working-class family in Molins de Rein, Spain, Margarita Xirgu came of age in a world where theater was a distant luxury. But when her family moved into the city during her teenage years, the stage called to her. She answered with defiance, intelligence, and passion.

Her first steps into performance came through radical theater collectives—groups that saw drama not just as entertainment, but as education, resistance, and revolution. These early experiences instilled in her the belief that theater could be a force for liberation. It was a belief she carried like armor, even as she faced public scorn for daring to be a woman in the spotlight—and a queer woman, no less.

Xirgu didn’t hide, but she did protect herself. She married a theater technician, Josep Arnall, more out of social necessity than love. Despite the gossip and the scorn, she forged ahead, building a career with grit and vision. Her fierce commitment to progressive ideals in a deeply conservative Spain made her be seen as a communist threat and earned her the nickname “Margarita la Roja” (Margarita the Red). The name was meant to mock her, but she wore it like a crown.

The Meeting That Changed Theater

By the time she met Lorca in 1926, Xirgu was already a star—unafraid, uncompromising, and burning with purpose. While Lorca may have been far from a household name, Xirgu saw something in him that she never saw in anyone else: a fire to match her own.

Together, they resurrected a historical martyr in Mariana Pineda, a play about a young woman executed for sewing a revolutionary flag. Their production was a political powder keg. The censors allowed it to be performed, but local governments boycotted or disrupted the play. Still, Xirgu refused to back down. She toured the show across Spain, declining to make a single cut despite repeated pressure.

During this time, Lorca left for the United States, but their artistic bond endured. When he returned to Spain in 1930, they reunited like flames drawn back together. Over the next few years, they created some of the most iconic plays in Spanish history. Lorca even wrote Yerma specifically for Xirgu, convinced that no other actress could summon the depth of grief and fury required for the role.

Their collaboration was not just professional—it was a creative symbiosis. Lorca found a muse who understood the heartache and hope in his words. Xirgu found a playwright who gave voice to everything she believed in. They were, in a sense, each other’s home.

War, Exile, and Loss

But that home would soon be shattered. In 1936, civil war broke out in Spain, and Xirgu made the painful decision to leave Spain. She set off for Latin America on a theater tour, urging Lorca to come with her. He refused. He believed in staying. In resisting.

She left with hope that they would reunite, that they would one day perform The House of Bernarda Alba together—Lorca’s latest play, written with Xirgu in mind for the lead. But only two months after its completion, Lorca was arrested and shot by Nationalist forces. His body was dumped in an unmarked grave.

Xirgu learned of his death just before going onstage to perform Yerma. The pain must have been unbearable. That night, instead of saying, “I myself have killed my son,” she cried out, “They have murdered my son.” The words tore through the theater. In that moment, art and life collapsed into one raw, searing truth.

Carrying the Torch

From that moment on, Spain was no longer home. As Franco’s dictatorship rose, Xirgu refused to return. She settled in Uruguay, where she continued performing, directing, and teaching. There, she led the Uruguayan National Theater and became a guiding light for generations of Latin American actors.

And most importantly, she kept Lorca’s voice alive.

While his plays were banned or butchered in Spain, Xirgu staged them uncut, unbowed. She taught them in classrooms. She infused them into the bones of new performers. She insisted that the themes Lorca wrote about—authoritarianism, repression, the silencing of women—were not just Spanish problems. They were universal. They were timeless.

“I did not go into exile to save myself,” she once said. “I went to save his words.”

A Legacy Worth Remembering

Xirgu never saw Spain again. She died in Montevideo in 1969. It wasn’t until after Franco’s death in 1975 that her body was returned to her homeland, where she was finally reburied with honors.

The Spanish press barely noticed her death. No obituary. No fanfare. But her legacy has never needed noise to endure.

In Latin America, she is remembered as the “godmother of the craft of acting,” a title bestowed by theater scholar Maria Delgado. And through her, Lorca’s voice continues to echo—not in whispers, but in full-throated declarations of truth, beauty, and defiance.

To look at Xirgu’s life as tragic is to miss the power of it. Hers was a life forged in fire, shaped by courage, and guided by the unshakable belief that art can change the world. She showed us that even in the face of fascism, exile, and grief, the theater can be a sanctuary—and a weapon.

Her story reminds us that we don’t just inherit the work of artists’ past. We are responsible for carrying it forward. Like Xirgu did for Lorca, we too can build a world where art, love, and freedom take center stage.

And until that world arrives, let our art be the lantern that lights the way.

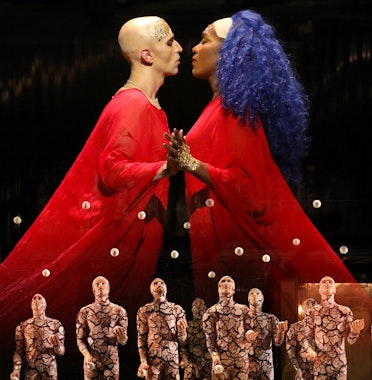

Interested in seeing Xirgu's story on our stage? Click here to get tickets for Ainadamar.

/03-cosi/_dsc0996_pr.jpg?format=auto&fit=crop&w=345&h=200&auto=format)