Blog

May 12, 2025

From Page to Stage: "Rigoletto"

In the annals of history, we can detect the echoes of people who we know existed, but whose full stories remain out of reach. The fewer details we know about these figures, the easier it becomes to reduce them to a title or simple description. A peasant is a peasant, a farmer a farmer, or a jester is just a jester.

But great writers don’t skim past these figures (or in the case of Rigoletto, a fictional jester inspired by real ones) without a second thought. Instead, they pause and ask: What does it feel like to be a jester? How do you make people laugh in a world that sees you as lesser? What does it cost you to risk your life for the amusement of those in power? These are the questions Victor Hugo asked when he imagined the life of a historical jester named Triboulet—a character who would go on to fascinate and inspire composer Giuseppe Verdi.

Triboulet wasn't just one person. He’s an amalgam of three jesters from French history, each serving in different courts. And to understand Verdi’s complex and conflicted protagonist, Rigoletto, we must first understand the jester who inspired it all.

The first Triboulet served under King René of Anjou in the late 1400s and was reportedly also a playwright. Triboulet II, a hunchback known for his cleverness, served King Louis XII in the early 1500s and died during his reign. Then came Triboulet III, who served at the tail end of Louis XII’s court and into the reign of King François I. Over time, the lives of these three individuals merged in the popular imagination into a single figure: a jester named Triboulet.

The version of Triboulet that most directly inspired Hugo and Verdi’s fictional jester drew heavily from the second Triboulet, remembered for his visible disability and dazzling wit. One epitaph described him as a gifted entertainer, mime, dancer, a poor musician (ouch!), and—most importantly—a master of words. The third Triboulet inherited this legacy and added even sharper humor. According to one well-known story, after offending a nobleman, the jester was sentenced to death. When King François I granted him the mercy of allowing him to choose how he would die, Triboulet replied, “I choose to die of old age.” So delighted was the king that he spared him.

The legend of Triboulet echoed through French history and eventually reached the ears of Victor Hugo, one of the most prominent writers of the 19th century. By the early 1830s, Hugo had helped usher in the Romantic movement in France. He had just published one of his seminal novels, The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831), and set his sights on another famous hunchbacked figure: Triboulet.

The result was Le roi s’amuse (The King Amuses Himself), which premiered on November 22, 1832. Hugo expected a hit. Instead, he ended up with the most controversial play of his career—one so politically charged and resonant in post-revolutionary France that it was banned after a single performance. Hugo fought the ban but could not overturn it. The play remained officially suppressed in France for 50 years.

Yet Le roi s’amuse refused to disappear. Its central character—a court jester twisted by cruelty yet filled with intelligence and deep love for his daughter—had too much gravity to be forgotten. Nearly two decades later, Triboulet’s story would resonate with another master of drama: Giuseppe Verdi.

By 1850, Verdi had become one of the most respected opera composers in Europe and was trusted to select his own subjects to set to music. Commissioned by Venice’s Teatro La Fenice for a new opera, he reunited with his frequent collaborator, librettist Francesco Maria Piave. At first, they considered adapting Kean by Alexandre Dumas fils but instead chose Hugo’s banned play, believing it offered more dramatic energy.

Verdi praised Le roi s’amuse in a letter to Piave, calling it “one of the greatest achievements of modern theater. The story is immense and includes a character worthy of the greatest stages in any era… Triboulet is a creation worthy of Shakespeare.”

Though Verdi may have found the perfect dramatic subject, he opened a can of worms with the censors. While Hugo’s play had not been formally banned in Italy, its reputation preceded it. Austrian authorities—who controlled much of northern Italy, including Venice—were wary of anything politically subversive.

Preparing for a censorship battle, Verdi urged Piave to find someone influential who could support their efforts. Piave enlisted Count Marcello, a well-connected Venetian nobleman known for his patronage of the arts. Marcello held the line in Venice while Verdi and Piave retreated to Verdi’s hometown of Busseto to prepare their defense.

At first, the signs looked promising. The censor assigned to the case, De Gorzkowski, was known for his love of opera and admiration for Verdi. Combined with Count Marcello’s support, it seemed there was hope. But in December 1850, De Gorzkowski denied permission to stage the opera, writing that protest or appeal would be useless. Many would have abandoned the project. Verdi doubled down.

Piave began revising the libretto to appease the censors, proposing major changes: downgrading the king to a duke, removing Triboulet’s hunchback, eliminating the curse, and altering the jester’s character. Though meant to help, these changes enraged Verdi. He rejected the softened version outright, unwilling to compromise the opera’s core themes.

Tensions between composer and librettist escalated. To mediate, Guglielmo Brenna—the secretary of La Fenice—wrote to De Gorzkowski, emphasizing the artistic value of allowing Verdi to depict King François I. Ultimately, De Gorzkowski’s passion for opera prevailed. In January 1851, he granted approval—provided that the king become the Duke of Mantua, Triboulet’s name changed, and the sexual encounter between Gilda and the Duke toned down.

Though still reluctant, Verdi accepted the compromise. He knew the heart of Triboulet would remain. Drawing inspiration from Jules-Édouard Alboize de Pujol’s play Rigoletti, ou Le dernier des fous. (Rigoletti, or The Last of the Fools), he chose the name Rigoletto for his protagonist. The name, reminiscent of the French rigoler (to laugh), carried echoes of the jester's tragic wit.

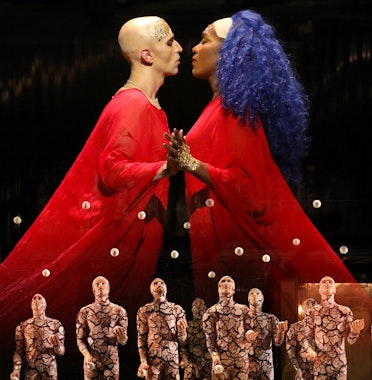

/05-Rigoletto/thedallasoperarigolettoflubackerhighlights-010_PR.jpg)

Amid the censorship turmoil, the opera still wasn’t finished. Verdi completed the score in Busseto on February 5, 1851—just weeks before its March 11 premiere. Paranoid about piracy or interference, he sent only partial excerpts to singers. The full score remained under lock and key, frustrating La Fenice’s management, who were left unsure what exactly they were producing.

To compensate, Piave quietly leaked information to help the theater begin set construction, even before the final act was completed. When Verdi arrived in Venice on February 19, he brought the full score at last—but continued to guard it closely. He locked the libretto away, personally supervised the copyists, and made musicians sign confidentiality agreements. Each singer had limited access to their parts. Most famously, tenor Raffaele Mirate—who sang the Duke—only received the iconic aria “La donna è mobile” a few days before the premiere and was forbidden to sing it outside rehearsal.

With so much chaos, La Fenice’s management feared Rigoletto would flop. But when the curtain fell on March 11, 1851, the audience erupted in applause. The double bill (with Giacomo Panizza’s Faust) had sold out the house. By the next morning, “La donna è mobile” was reportedly being sung in the streets of Venice.

Rigoletto became an instant success and a mainstay of the Italian operatic repertoire. By 1855, it had been performed throughout Europe and the Americas—from London to New York, Montevideo to Havana. Verdi’s instincts were right. His fight for the integrity of the story, even amid censorship and creative conflict, paid off. Later in life, Verdi would call Rigoletto “the best subject I’ve ever set to music.”

If you want to see Rigoletto on stage, get tickets for staging by clicking here.

/03-cosi/_dsc0996_pr.jpg?format=auto&fit=crop&w=345&h=200&auto=format)